Lessons From Jack Ma

WPP hits 30 next month. Rather a lot has changed since 1985 when, along with my then business partner, I invested in a manufacturer of wire shopping baskets and teapots.

If I had to reduce those changes to a single phrase, it would be “geography and technology”. Thirty years ago China’s GDP was about $300 billion; today it’s more than $10 trillion. Thirty years ago Tim Berners-Lee had yet to invent the web; today Google is arguably the most valuable brand in the world.

The West is still in denial about the rising power of the so-called emerging economies (an outmoded expression, since the biggest have not only emerged, but left more mature markets trailing in their wake).

Many seem to want China to fail, which is the definition of shooting yourself in the foot, because the global economy needs it to succeed. Others point to slowing growth of “only” seven per cent.

I remain an unabashed Chinese bull. It’s now our third biggest market after the US and UK, with revenues of more than $1.5 billion and some 15,000 people.

There is deep complacency and condescension in the Western view of Chinese technology firms. “All they do is copy and steal” is the fashionable thing to say. That, by the way, is what we said about Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea. My experience is that many Chinese CEOs understand digital technology better than we do.

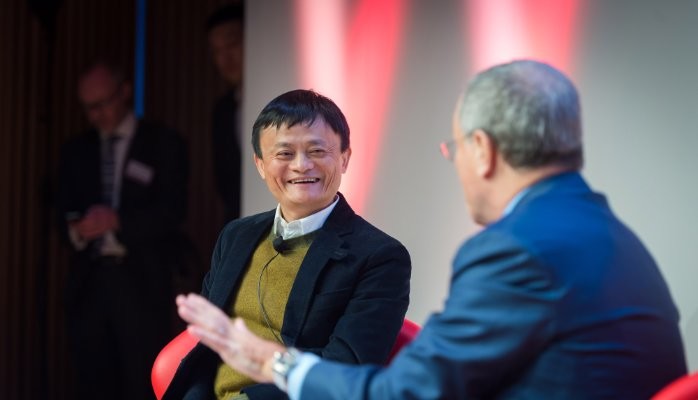

A few weeks ago I attended the GREAT Festival of Creativity in Shanghai – put on by the UK Government to showcase British creative businesses to the Chinese market. As part of the event I did my poor man’s impression of Charlie Rose and interviewed Jack Ma, the founder and Executive Chairman of Alibaba – the e-commerce juggernaut with a market capitalisation of more than $200 billion.

Ma is a rockstar in China (and becoming one everywhere else, too). At the end of the session a large group of admirers from the audience rushed up the stage. If I’d been in any doubt as to the object of their interest, it didn’t last long, as I was unceremoniously bundled out of the way by the mob.

Alibaba’s aim is simple, and jaw-droppingly ambitious. It is, as Ma puts it, “to be the infrastructure of commerce in China”. Its focus is on small businesses, helping them to sell through its Taobao marketplace, providing financial services through Alipay and offering logistical support through its cloud computing and data platform.

The received wisdom is that Chinese companies can’t and don’t want to expand internationally. Not so. “We’re an internet company that happens to be in China,” says Ma. “Our vision is to help small businesses globally.”

Although less than five per cent of the company’s revenues currently come from international markets, Ma wants it to be 50. He says Europe will be first, followed by Japan, Korea, India and Indonesia. Xiaomi, the four-year-old, $45-billion-valued, Chinese smartphone and over-the-top TV box maker, has similar geographical ambitions: India, Indonesia and Brazil.

Ma has looked at the US market, but concluded that it’s too difficult – at least in the short-term. “Everyone expects us to go to America… We want to go to America and help American farmers, American small businesses, helping them to sell to China [but] I personally think we can do a lot more in Europe than in America.”

Nonetheless, Alibaba has established a foothold in the States through a series of investments in start-ups including video chat firm Tango and car-sharing company Lyft. As of March it also has a data centre (in Silicon Valley) to attract new cloud computing customers.

Ma says the start-up stakes – through a dedicated investments operation in San Francisco – are “contributions” intended “to give thanks” to American tech innovation. But with bets like the rumoured $200 million in Snapchat, reported last month, it’s fair to assume the motive is not entirely altruistic.

While highly respectful of US tech leaders, Ma doesn’t pull his punches when talking about the competition. Amazon “was a good model in 1990-something”; eBay “ran away”.

Answering the accusation of copying, he says China is adding value to global technology, but it’s “only just started”. He chastises anyone within his own company who complains that others have stolen their technology: “It means we’re not fast enough. We’re not innovative enough. The losers say ‘they steal’. The winners say ‘I run faster’.”

Many in the West choose to characterise Chinese companies as a threat, which in some respects they are – just as any disruptor is to an incumbent. In our own line of business, Blue Focus, the Shenzhen-listed firm founded by Oscar Zhao in 1996, has high hopes of global expansion. Rather than worrying about invaders from the East, however, a more constructive approach would be to learn from entrepreneurs like Jack Ma, and start taking a few risks.

The greatest threat to long-term global economic development is the prevailing culture of chronic risk aversion among corporates. Too many are focused on their boots instead of the horizon, minutely managing costs while failing to invest sufficiently in top-line growth. The global cash pile, sitting uninvested on balance sheets, has reached mountainous proportions.

Growth is sluggish, inflation is at an all-time low and brands have no pricing power. Little surprise, then, that consolidation continues to be the name of the game, across all sectors – from food and beverages to construction, pharmaceuticals and media.

The Heinz-Kraft merger, for example, appears to be cost- rather than revenue-driven, at least in the short- to medium-term: good news for the finance and procurement departments, less so for marketing and product development.

Consolidation is not limited to client companies or media owners. Among our competitors in marketing services, the smaller groups like IPG are those under the most immediate threat of being swallowed up (perhaps by Dentsu, if the collapse in their overseas margins since buying Aegis hasn’t spoilt their appetite).

One thing that hasn’t changed in the last three decades is this industry’s infinite capacity to surprise, but, even so, tie-ups between the leading players seem unlikely for now. Recent history has shown that, whatever the problems facing each party, so-called mergers of equals are not the most elegant solution.

This article first appeared in the Sunday Telegraph

Photo: UKTI

Let's make advertising useful - not annoying.

8ySo, in 15 years we'll be talking about India in the same way then?

M&A Private Equity

8y"The West is still in denial about the rising power of the so-called emerging economies"